Some elderly folk who remember the 1950s will tell you that the decade was a more civilised time than today. Behaviour was better, dishonesty was rare, and the commercial pressures that cause so many of modern society’s problems had yet to arrive. Don’t believe a word.

When the UK bike press was let loose on the new 1954-model T110 Tiger for the first time, Triumph made every effort to ensure that their machine had a chance to shine. Bernal Osborne, editor of the influential Motorcycling magazine, was allowed out on the 650cc sportster and, after a morning spent on the roads around Triumph’s factory at Meriden, he returned to declare himself impressed by its smooth, flexible parallel-twin engine.

Osborne was then treated to a long lunch with no less a figure than legendary Triumph boss Edward Turner, before taking possession of the T110 once again for an afternoon’s speed-testing at a nearby proving ground. Here, the Triumph again excelled – clocking an impressive 182km/h with standard carburettor and air-filter, and an outstanding 187.5km/h after rejetting of its Amal carb. “Versatility – that was the outstanding quality of the Triumph T110,” enthused the magazine’s headline the following week.

What Osborne did not know, and was only revealed many years later by former Triumph employee Hughie Hancox (who had become a leading classic bike restorer), was that his lunch with Turner had been arranged to give Triumph’s engineers time to tweak the Tiger. Hancox and two colleagues had replaced the standard camshafts and cam followers with a pair of Triumph’s famous E3134 high-performance camshafts and R (for Racing) followers, giving a significant performance increase that helped gain the T110 a reputation as the British industry’s hottest new sports bike.

Tuning of test-bikes and other dubious manoeuvres were rumoured to have taken place on a regular basis in the 1950s and later, but Triumph’s outrageous (and successful) cheating is an indication of what an important bike the T110 Tiger was back in 1954. When it was introduced in that year the T110 became Triumph’s top-of-the-range model. It was an uprated version of the popular 650 Thunderbird featuring a tuned engine plus Triumph’s first ever frame with the now familiar swinging-arm and twin-shock rear suspension.

The T110 was produced largely at the request of Triumph’s customers and dealers in the big American market, where racing and high-performance were more important than in Europe – and where tuned 650cc twins were being ridden and raced with great success. Compared to the Thunderbird, the Tiger had sportier cams, higher compression ratio, modified engine porting and a larger 11/8 in Amal carburettor, all of which combined to give a peak output of 42hp at 6500rpm.

That put the Triumph ahead of its predecessors, even if the T110’s true top speed was a little less than the 110mph [176km/h] suggested by its name, let alone that tuning-assisted figure of 11.5km/h more. The bike’s performance made it very competitive at the time, and the Triumph quickly became a success on both sides of the Atlantic. But it was not without faults, most notably overheating of the engine, resultant distortion of the old-style iron cylinder head (which led to blown head gaskets and loss of power), and, on the chassis front, a high-speed weave caused mainly by lack of bracing at the swing-arm.

Those problems and others led to a series of modifications over the years, notably the adoption of a more heat-resistant alloy cylinder head in 1956. Two years later Triumph introduced the so-called “slick-shift” gearbox, which allowed clutchless gear changes but was unpopular with many riders, and also offered the option of a twin-carb cylinder head. The major chassis updates came in 1960, with the change from single- to twin-downtube frame, and the adoption of Triumph’s distinctive “bathtub” rear enclosure.

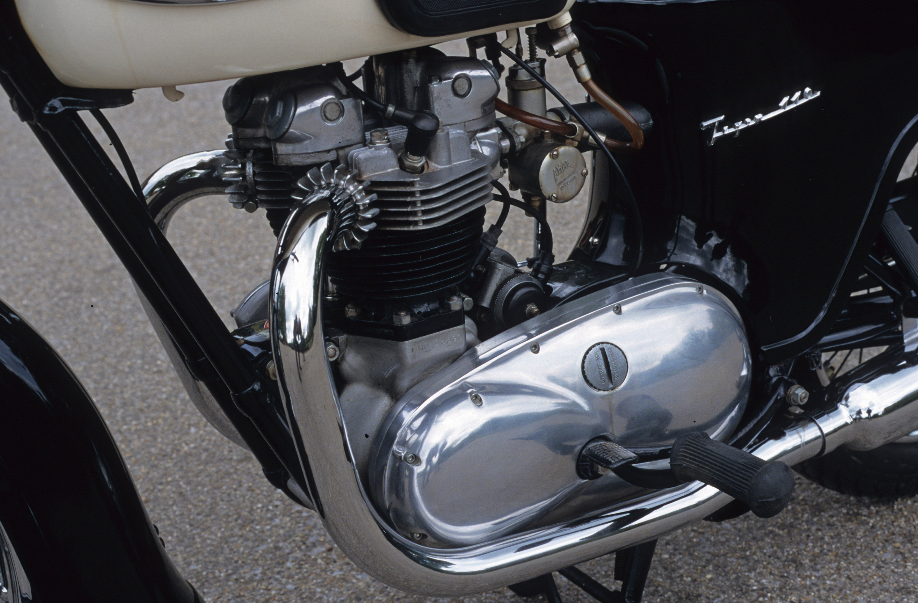

Which brings us to this bike, a neat and very original model from 1960, finished in black and white, and with that bathtub, intended to be practical and easy to clean, at the rear end. The bathtub – so called because of its similarity to an upside-down tin bath – had been designed by Edward Turner, and introduced on the 350cc Twenty-one model in 1957. The style had not proved popular but was nevertheless added to the T110 in 1960. It emphasised that the Tiger was no longer Triumph’s sports model, having lost that title to the more powerful twin-carb T120 Bonneville, which had been launched the previous year.

The T110 might have been slightly down on power and speed to a well-fettled Bonneville when new, but many Triumph enthusiasts insist that the single-carb bike is easier to keep in tune, and thus just as quick most of the time. This bike was looking good in middle-age. There were a few slight rust patches around its tank badges, and its chrome didn’t exactly shine like new, but the Triumph was basically in very clean and original condition.

Its engine required a tickle of the Amal and a harder-than-normal prod on the kickstart to get it going – the latter suggesting that the original T110’s relatively high 8.5:1 compression ratio had not been reduced over the years – but settled down to an easy tickover with a typical Triumph pushrod rattle audible above the sound of the twin pipes. At about 190kg with fuel the Tiger is as light as a modern sports bike, and felt even lighter thanks to its low seat and centre of gravity.

View from the saddle is anything but modern, thanks to period features – more 1950s than ’60s – such as the headlamp nacelle containing a black-faced Smiths speedometer, ammeter, light switch and engine kill-button, and the fuel tank’s chromed luggage rack and rubber knee-grips. The right-foot gearchange added further old-fashioned feel, although at least its pattern was one-down, three-up in the normal way.

One quirk of the gearbox was that if you held your foot down on the lever with the bike in gear, you could let go of the clutch without stalling – useful when turning left in the days before indicators. (Or maybe just an admission that neutral was often hard to find…) But the clutch was light, and I headed off for a gentle day’s ride the old Triumph felt pleasantly torquey, smooth and laid-back, chuffing along happily at 100km/h as though it would be happy to do so all day.

Acceleration at low and medium speeds was reasonably good, too, the Triumph pulling hard enough to be fun on minor roads, where its gearbox proved reliable provided it wasn’t hurried. On wider roads an indicated 110km/h proved about the Tiger’s comfortable limit, as vibes coming through the tank began to be annoying at much above that figure. But there was plenty of power in hand for short bursts of speed, even if I though the better of trying to push this ageing bike over the 160km/h mark, the magic “ton”.

Back in its heyday the road-testers had no such hesitation, of course, and the T110 provided them with performance that was a match for almost anything on two wheels. “Few road burners, in truth, would ask for a higher cruising speed than the Triumph eagerly provides,” reported one biking newspaper. “Acceleration through the gears was scintillating and carburation clean. Even at an indicated 80mph [128km/h] an exhilarating surge forward could be produced simply by snapping the throttle wide open. A speed of 80mph could be held on half throttle, while a sustained 90mph [144km/h] proved to be quite within the model’s capabilities.”

That particular T110 test also went on to say that “an appreciable amount of oil leaked past the gearbox mainshaft onto the rear tyre. Also, when performance data were being obtained the ammeter failed, possibly as a result of vibration.” Triumph’s twins were good performers by the standards of their day, but you couldn’t thrash them without risking problems. That bike also misfired in the wet, a common British-bike failing that was not confined to Triumphs.

The T110’s handling was highly regarded in its day, particularly that of this 1960 model. Its new twin-downtube frame and revised geometry gave slightly heavier steering and made the later Tiger more stable at high speed than the earlier models. This bike didn’t wobble in a straight line, but both ends lacked damping and the soft front forks dived every time I touched the front brake.

Stopping power was inevitably feeble compared to almost any modern bike, although both brakes were regarded as good in their time, apart from the front drum’s tendency to fade after repeated high-speed use. This bike’s main braking-related problem was the loud squeal of protest that the 200mm front drum made ever time it was used. After a while this was enough to make me ignore it and rely on the rather sharp rear drum whenever possible.

One thing I couldn’t complain about were the Metzeler front and Avon rear tyres, which gave levels of grip that a hard-riding T110 owner could only have dreamed about when it was new. Plenty of riders used this bike hard, too, back in 1960, although by then the Tiger’s best days were already in the past. The model’s high point had come two years earlier in 1958, when Mike Hailwood and Dan Shorey had teamed up to win the prestigious Thruxton 500-mile production race.

The new T120 Bonneville’s arrival a year later ended the Tiger’s reign as Triumph’s No. 1 sports machine, and in 1961 the single-carb bike was dropped from the line-up. The T110 Tiger was gone, but its lively performance had done much for Triumph’s sales and reputation. Aided, of course, by some excellent publicity – however dubiously some of it had been generated.

| Triumph T110 Tiger | |

| Engine type | Aircooled pushrod, 2-valve parallel twin |

| Displacement | 649cc |

| Bore x stroke | 71 x 82mm |

| Compression ratio | 8.5:1 |

| Carburation | 11/8 in Amal |

| Claimed power | 42hp @ 6500rpm |

| Transmission | 4-speed |

| Electrics | 6V battery; 30/24W headlamp |

| Frame | Tubular steel duplex cradle |

| Front suspension | Telescopic, no adjustment |

| Rear suspension | Twin shock absorbers, 3-way adjustable preload |

| Front brake | 200mm sls drum |

| Rear brake | 178mm sls drum |

| Front tyre | 3.25 x 18in (Metzeler ME11) |

| Rear tyre | 3.50 x 18in (Avon Supreme) |

| Wheelbase | 1384mm |

| Seat height | 787mm |

| Fuel capacity | 18 litres |

| Weight | 190kg wet |